Somnath Temple Prabhas Patan,Gujarat

The Somnath temple, also called Somanātha temple or Deo Patan, is a Hindu temple located in Prabhas Patan, Veraval in Gujarat, India. It is one of the most sacred pilgrimage sites for Hindus and is the first among the twelve jyotirlinga shrines of Shiva. It is unclear when the first version of the Somnath temple was built with estimates varying between the early centuries of the 1st-millennium to about the 9th-century CE. The temple is not mentioned in ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism as Somnath nomenclature but the “Prabhasa-Pattana” (Prabhas Patan) is mentioned as a tirtha (pilgrimage site), where this temple exists. For example, the Mahabharata in Chapters 109, 118 and 119 of the Book Three (Vana Parva), and Sections 10.45 and 10.78 of the Bhagavata Purana state Prabhasa to be a tirtha on the coastline of Saurashtra.

The temple was reconstructed several times in the past after repeated destruction by multiple Muslim invaders and rulers, notably starting from an attack by Mahmud Ghazni in the 11th century.

The Somnath temple was actively studied by colonial era historians and archaeologists in the 19th- and early 20th-century, when its ruins illustrated a historic Hindu temple in the process of being converted into an Islamic mosque. After India’s independence, those ruins were demolished and the present Somnath temple was reconstructed in the Māru-Gurjara style of Hindu temple architecture. The contemporary Somnath temple’s reconstruction was started under the orders of the first Deputy Prime Minister of India Vallabhbhai Patel after receiving approval for reconstruction from Mahatma Gandhi. The reconstruction was completed in May 1951 after his death.

Location

The Somnath temple is located along the coastline in Prabhas Patan, Veraval, Saurashtra region of Gujarat. It is about 400 kilometres (249 mi) southwest of Ahmedabad, 82 kilometres (51 mi) south of Junagadh – another major archaeological and pilgrimage site in Gujarat. It is about 7 kilometres (4 mi) southeast of the Veraval railway junction, about 130 kilometres (81 mi) southeast of the Porbandar airport and about 85 kilometres (53 mi) west of the Diu airport.

The Somnath temple is located close to the ancient trading port of Veraval, one of three in Gujarat from where Indian merchants departed to trade goods. The 11th-century Persian historian Al-Biruni states that Somnath has become so famous because “it was the harbor for seafaring people, and a station for those who went to and fro between Sufala in the country of Zanj (east Africa) and China”. Combined with its repute as an eminent pilgrimage site, its location was well known to the kingdoms within the Indian subcontinent.[17][18] Literature and epigraphical evidence suggests that the medieval era Veraval port was also actively trading with the Middle East and Southeast Asia. This brought wealth and fame to the Veraval area as well as the temple.

The site of Prabhas Patan was occupied during the Indus Valley Civilisation, 2000–1200 BCE. It was one of very few sites in the Junagadh district to be so occupied. After abandonment in 1200 BCE, it was reoccupied in 400 BCE and continued into the historical period. Prabhas is also close to the other sites similarly occupied: Junagadh, Dwarka, Padri and Bharuch.

Nomenclature and significance

Somnath means “Lord of the Soma” or “moon”. The site is also called Prabhasa (“place of splendor”). Somnath temple has been a jyotirlinga site for the Hindus, and a holy place of pilgrimage (tirtha ). It is one of five most revered sites on the seacoast of India, along with the nearby Dvaraka in Gujarat, Puri in Odisha, Rameshvaram and Chidambaram in Tamil Nadu.

Jyotirlinga

Many Hindu texts provide a list of the most sacred Shiva pilgrimage sites, along with a guide for visiting the site. The best known were the Mahatmya genre of texts. Of these, Somnatha temple tops the list of jyotirlingas in the Jnanasamhita – chapter 13 of the Shiva Purana, and the oldest known text with a list of jyotirlingas. Other texts include the Varanasi Mahatmya (found in Skanda Purana), the Shatarudra Samhita and the Kothirudra Samhita. All either directly mention the Somnath temple as the number one of twelve sites, or call the top temple as “Somesvara” in Saurashtra – a synonymous term for this site in these texts.[26][27][28][note 3] The exact date of these texts is unknown, but based on references they make to other texts and ancient poets or scholars, these have been generally dated between the 10th- and 12th-century, with some dating it much earlier and others a bit later.

Scriptural Mentions

The Somnath temple is not mentioned in ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism, but the “Prabhasa-Pattana” is mentioned as a tirtha (pilgrimage site).For example, the Mahabharata (c. 400 CE) in Chapters 109, 118 and 119 of the Book Three (Vana Parva), and Sections 10.45 and 10.78 of the Bhagavata Purana state Prabhasa to be a tirtha on the coastline of Saurashtra.

Alf Hiltebeitel – a Sanskrit scholar known for his translations and studies on Indic texts including the Mahabharata, states that the appropriate context for the legends and mythologies in the Mahabharata are the Vedic mythologies which it borrowed, integrated and re-adapted for its times and its audience. The Brahmana layer of the Vedic literature already mention tirtha related to the Saraswati river. However, given the river was nowhere to be seen when the Mahabharata was compiled and finalized, the Saraswati legend was modified. It vanishes into an underground river, then emerges as an underground river at holy sites for sangam (confluence) already popular with the Hindus. The Mahabharata then integrates the Saraswati legend of the Vedic lore with the Prabhasa tirtha, states Hiltebeitel.[31] The critical editions of the Mahabharata, in several chapters and books mentions that this “Prabhasa” is at a coastline near Dvaraka. It is described as a sacred site where Arjuna and Balarama go on tirtha, a site where Lord Krishna chooses to go and spends his final days, then dies.

Catherine Ludvik – a Religious Studies and Sanskrit scholar, concurs with Hiltebeitel. She states that the Mahabharata mythologies borrow from the Vedic texts but modify them from Brahmin-centered “sacrificial rituals” to tirtha rituals that are available to everyone – the intended audience of the great epic. More specifically, she states that the sacrificial sessions along the Saraswati river found in sections such as of Pancavimsa Brahmana were modified to tirtha sites in the context of the Saraswati river in sections of Vana Parva and Shalya Parva. Thus the mythology of Prabhasa in the Mahabharata, which it states to be “by the sea, near Dwaraka”. This signifies an expanded context of pilgrimage as a “Vedic ritual equivalent”, integrating Prabhasa that must have been already important as a tirtha site when the Vana Parva and Shalya Parva compilation was complete.

The 5th-century poem Raghuvamsa of Kalidasa mentions some of revered Shiva pilgrimage sites of his times. It includes Banaras (Varanasi), Mahakala-Ujjain, Tryambaka, Prayaga, Pushkara, Gokarna and Somnatha-Prabhasa. This list of Kalidasa gives a “clear indication of tirthas celebrated in his day”, states Diana Eck – an Indologist known for her publications on historic Indian pilgrimage sites.

History

The site of Somnath has been a pilgrimage site from ancient times on account of being a Triveni Sangam (the confluence of three rivers: Kapila, Hiran and Saraswati). Soma, the Moon god, is believed to have lost his lustre due to a curse, and he bathed in the Sarasvati River at this site to regain it. The result is said to be the waxing and waning of the moon. The name of the town, Prabhas, meaning lustre, as well as the alternative names Someshvar and Somnath (“the lord of the moon” or “the moon god”), arise from this tradition.

The name Someshvara begins to appear starting in the 9th century. The Gurjara-Pratihara king Nagabhata II (r. 805–833) recorded that he has visited tirthas in Saurashtra, including Someshvara.[36] Romila Thapar states that this does not imply the existence of a temple, but rather that it was a pilgrimage site (tirtha). The Chaulukya (Solanki) king Mularaja possibly built the first temple for Soma at the site sometime before 997 CE, even though some historians believe that he may have renovated a smaller earlier temple.

The post-1950 excavations of the Somnath site have unearthed the earliest known version of the Somnath temple. The excavations showed the foundations of a 10th-century temple, notable broken parts and details of a major, well decorated version of a temple. Madhusudan Dhaky believes it to have been the one that was destroyed by Mahmud of Ghazni. B.K. Thapar, the archaeologist who did the excavation, stated that there was definitely a temple structure at Somnath-Patan in the 9th-century, but none before.

In 1026, during the reign of Bhima I, the Turkic Muslim ruler Mahmud of Ghazni raided and plundered the Somnath temple, broke its jyotirlinga. He took away a booty of 20 million dinars. According to Romila Thapar, relying on a 1038 inscription of a Kadamba king of Goa, the condition of Somnath temple in 1026 after Ghazni’s is unclear because the inscription is “puzzlingly silent” about Ghazni’s raid or temple’s condition. This inscription, states Thapar, could suggest that instead of destruction it may have been a desecration because the temple seems to have been repaired quickly within twelve years and was an active pilgrimage site by 1038.

The raid of 1026 by the Turkic Muslim ruler Mahmud of Ghazni is confirmed by the 11th-century Persian historian Al-Biruni, who worked in the court of Mahmud, who accompanied Mahmud’s troops between 1017 and 1030 CE on some occasions, and who lived in the northwest Indian subcontinent region – over regular intervals, though not continuously. The invasion of Somnath site in 1026 CE is also confirmed by other Islamic historians such as Gardizi, Ibn Zafir and Ibn al-Athir. However, two Persian sources – one by adh-Dhahabi and other by al-Yafi’i – state it as 1027 CE, which is likely incorrect and late by a year, according to Khan – a scholar known for his studies on Al-Biruni and other Persian historians. According to Al-Biruni:

The location of the Somnath temple was a little less than three miles west of the mouth of the river Sarasvati. The temple was situated on the coast of the Indian ocean so that at the time of flow the idol was bathed by its water. Thus that moon was perpetually occupied in bathing the idol and serving it.”

Al-Biruni states that Mahmud destroyed the Somnath temple. He states Mahmud’s motives as, “raids undertaken with a view to plunder and to satisfy the righteous iconoclasm of a true Muslim… [he] returned to Ghazna laden with costly spoils from the Hindu temples.” Al-Biruni obliquely criticizes these raids for “ruining the prosperity” of India, creating antagonism among the Hindus for “all foreigners”, and triggering an exodus of scholars of Hindu sciences far away from regions “conquered by us”. Mahmud launched many plunder campaigns into India, including one that included the sack of Somnath temple.

According to Jamal Malik – a South Asian history and Islamic Studies scholar, “the destruction of Somnath temple, a well known place of pilgrimage in Gujarat in 1026, played a major role in creating Mahmud as an “icon of Islam”, the sack of this temple became “a crucial topic in Persian stories of Islamic iconoclasm”. Many Muslim historians and scholars in and after the 11th-century included the destruction of Somnath as a righteous exemplary deed in their publications. It inspired the Persian side with a cultural memory of Somnath’s destruction through “epics of conquest”, while to the Hindu side, Somnath inspired tales of recovery, rebuilding and “epics of resistance”. These tales and chronicles in Persia elevated Mahmud as “the exemplary hero and Islamic warrior for the Muslims”, states Malik, while in India Mahmud emerged as the exemplary “arch-enemy”.

Powerful legends with intricate detail developed in the Turko-Persian literature regarding Mahmud’s raid,[50] which “electrified” the Muslim world according to scholar Meenakshi Jain. According to historian Cynthia Talbot, a later tradition states that “50,000 devotees lost their lives in trying to stop Mahmud” during his sack of Somnath temple.[52] According to Thapar, the “50000 killed” is a boastful claim that is “constantly reiterated” in Muslim texts, and becomes a “formulaic” figure of deaths to help highlight “Mahmud’s legitimacy in the eyes of established Islam”.

Kumarapala (r. 1143–72) rebuilt the Somnath temple in “excellent stone and studded it with jewels,” according to an inscription in 1169. He replaced a decaying wooden temple.

During its 1299 invasion of Gujarat, Alauddin Khalji’s army, led by Ulugh Khan, defeated the Vaghela king Karna, and sacked the Somnath temple. Legends in the later texts Kanhadade Prabandha (15th century) and Nainsi ri Khyat (17th century) state that the Jalore ruler Kanhadadeva later recovered the Somnath idol and freed the Hindu prisoners, after an attack on the Delhi army near Jalore. However, other sources state that the idol was taken to Delhi, where it was thrown to be trampled under the feet of Muslims. These sources include the contemporary and near-contemporary texts including Amir Khusrau’s Khazainul-Futuh, Ziauddin Barani’s Tarikh-i-Firuz Shahi and Jinaprabha Suri’s Vividha-tirtha-kalpa. It is possible that the story of Kanhadadeva’s rescue of the Somnath idol is a fabrication by the later writers. Alternatively, it is possible that the Khalji army was taking multiple idols to Delhi, and Kanhadadeva’s army retrieved one of them.

The temple was rebuilt by Mahipala I, the Chudasama king of Saurashtra in 1308 and the lingam was installed by his son Khengara sometime between 1331 and 1351.[61] As late as the 14th century, Gujarati Muslim pilgrims were noted by Amir Khusrow to stop at that temple to pay their respects before departing for the Hajj pilgrimage.In 1395, the temple was destroyed for the third time by Zafar Khan, the last governor of Gujarat under the Delhi Sultanate and later founder of Gujarat Sultanate. In 1451, it was desecrated by Mahmud Begada, the Sultan of Gujarat.

By 1665, the temple, one of many, was ordered to be destroyed by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. In 1702, he ordered that if Hindus revived worship there, it should be demolished completely.

British Raj

In 1842, Edward Law, 1st Earl of Ellenborough issued his Proclamation of the Gates, in which he ordered the British army in Afghanistan to return via Ghazni and bring back to India the sandalwood gates from the tomb of Mahmud of Ghazni in Ghazni, Afghanistan. These were believed to have been taken by Mahmud from Somnath. Under Ellenborough’s instruction, General William Nott removed the gates in September 1842. A whole sepoy regiment, the 6th Jat Light Infantry, was detailed to carry the gates back to India in triumph. However, on arrival, they were found not to be of Gujarati or Indian design, and not of Sandalwood, but of Deodar wood (native to Ghazni) and therefore not authentic to Somnath.[68][69] They were placed in the arsenal store-room of the Agra Fort where they still lie to the present day. There was a debate in the House of Commons in London in 1843 on the question of the gates of the temple and Ellenbourough’s role in the affair. After much crossfire between the British Government and the opposition, all of the facts as we know them were laid out.

In the 19th century novel The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, the diamond of the title is presumed to have been stolen from the temple at Somnath and, according to the historian Romila Thapar, reflects the interest aroused in Britain by the gates. Her recent work on Somnath examines the evolution of the historiographies about the legendary Gujarat temple.

Reconstruction during 1950–1951

Before independence, Veraval was part of the Junagadh State, whose ruler had acceded to Pakistan in 1947. India contested the accession and annexed the state after holding a referendum. India’s Deputy Prime Minister Vallabhbhai Patel came to Junagadh on 12 November 1947 to direct the stabilization of the state by the Indian Army, at which time he ordered the reconstruction of the Somnath temple.

When Patel, K. M. Munshi and other leaders of the Congress went to Mahatma Gandhi with their proposal to reconstruct the Somnath temple, Gandhi blessed the move but suggested that the funds for the construction should be collected from the public, and the temple should not be funded by the state. He expressed that he was proud to associate himself to the project of renovation of the temple.[76] However, soon both Gandhi and Sardar Patel died, and the task of reconstruction of the temple continued under Munshi, who was the Minister for Food and Civil Supplies, Government of India headed by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

The ruins were pulled down in October 1950. The mosque present at that site was shifted few kilometres away by using construction vehicles. On 11 May 1951, Rajendra Prasad, the first President of the Republic of India, invited by K M Munshi, performed the installation ceremony for the temple.

Description

Temple architecture

Pre-11th century temple

The floor plan and ruins of a pre-1000 CE temple were unearthed during the archaeological excavations led by B.K. Thapar. Most of the temple is lost, but the remains of the foundation, the lower structure as well as pieces of the temple ruins suggest an “exquisitely carved, rich” temple. According to Dhaky – a scholar of Indian temple architecture, this is the earliest known version of the Somnath temple. It was, what historic Sanskrit vastu sastra texts call the tri-anga sandhara prasada. Its garbhagriha (sanctum) was connected to a mukhamandapa (entrance hall) and gudhamandapa.

The temple opened to the east. The stylobate of this destroyed temple had two parts: the 3 feet high pitha-socle and the vedibandha-podium. The pitha had a tall bhitta, joined to the jadyakumbha, ornamented with what Dhaky calls “crisp and charming foliage pattern”. The kumbha of the Vedibandha had a Surasenaka with a niche that contained the figure of Lakulisa – this evidence affirms that the lost temple was a Shiva temple.

The excavations yielded pieces of one at the western end, which suggests that the kumbhas were aligned to the entire wall. Above the kalaga moulding was an antarapatta, states Dhaky, but no information is available to determine its design or ornamentation. The surviving fragment of the kapotapali that was discovered suggests that at “intervals, it was decorated with contra-posed half thakaras, with large, elegant, and carefully shaped gagarakas in suspension graced the lower edge of the kapotapali”, states Dhaky. The garbhagriha had a vedibandha, possibly with a two-layered jangha with images on the main face showing the influence of the late Maha-Maru style. Another fragment found had a “beautifully moulded rounded pillarette and a ribbed khuraccadya-awning topped the khattaka”.

The mukhachatuski, states Dhaky, likely broke and fell immediately after the destructive hit by Mahmud’s troops. These fragments suffered no further erosion or damage one would normally expect, likely because it was left in the foundation pit of the new Somnath temple that was rebuilt quickly after Mahmud left. The “quality of craftsmanship” in these fragments is “indeed high”, the carvings of the lost temple were “rich and exquisite”, states Dhaky. Further, a few pieces have an inscription fragment in the 10th-century characters – which suggests that this part of the temple or the entire temple was built in the 10th-century.

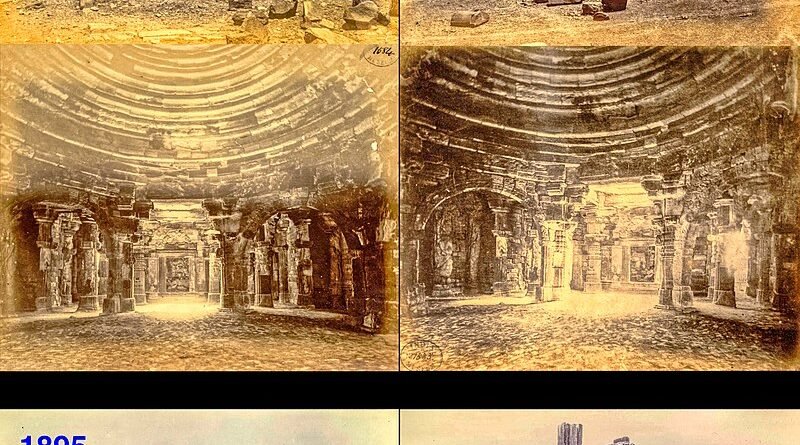

19th-century ruined Somnath temple partly converted into mosque

The efforts of colonial era archaeologists, photographers and surveyors have yielded several reports on the architecture and arts seen at the Somnath temple ruins in the 19th century. The earliest survey reports of Somnath temple and the condition of the Somanatha-Patan-Veraval town in the 19th-century were published between 1830 and 1850 by British officers and scholars. Alexander Burnes surveyed the site in 1830, calling Somnath site as “far-famed temple and city”. He wrote:

The great temple of Somnath stands on a rising ground on the north-west side of Pattan, inside the walls, and is only separated by them from the sea. It may be scen from a distance of twenty-five miles. It is a massy stone building, evidently of some antiquity. Unlike Hindu temples gencrally, it consists of three domes, the first of which forms the roof of the entrance, the second is the interior of the temple, the third was the sanctum sanctorum, wherein were deposited the riches of Hindi devotion. The two external domes are diminutive: the central one has an elevation of more than thirty feet, tapering to the summit in fourteen steps, and is about forty feet in diameter. It is perfect, but the images which have once adorned both the interior and exterior of the building are mutilated, and the black polished stones which formed its floor have been removed by the citizens for less pious purposes. Two marble slabs, with sentences from the Koran, and inscriptions regarding Mangrol Isa, point out where that Mohammedan worthy rests. They arc on the western side of the city, and the place is still frequented by the devout Moslem. Near it is a cupola, supported on pillars, to mark the grave of the sultan’s cashkeeper, with many others; and the whole city is encircled by the remains of mosques, and one vast cemetery, ‘The field of battle, where the “infidels” were conquered, is also pointed out, and the massy walls, excavated ditch, paved streets, and squared-stone buildings of Pattan itself, proclaim its former greatness. At present the city is a perfect ruin, its houses are nearly unoccupied and but for a new and substantial temple, erected to house the god of Somnath by that wonderful woman, Ahalya Bai, the wife of Holkar.

He states that the site shows how the temple had been changed into a Muslim structure with arch, these sections had been reconstructed with “mutilated pieces of the temple’s exterior” and “inverted Hindu images”. Such modifications in the dilapidated Somnath temple to make it into a “Mohammedan sanctuary”, states Burnes, is “proof of Mohammedan devastation” of this site. Burnes also summarized some of the mythologies he heard, the bitter communal sentiments and accusations, as well as the statements by garrisoned “Arabs of the Junagar [Junagadh] chief” about their victories in this “infidel land”.

The survey report of Captain Postans was published in 1846. He states:

Pattan, and all the part of the country wherein it is situated, is now under a Mohamedan ruler, the Nawab of Junagadh, and the city itself offers the most curious specimen of any I have ever seen of its original Hindu character, preserved throughout its walls, gates, and buildings, despite Mohammedan innovations and a studied attempt to obliterate the traces of paganism ; even the very musjids, which are here and there encountered in the town, have been raised by materials from the sacred edifices of the conquered, or, as it is said by the historians of Sindh, “the true believers turned the temples of the idol worshippers into places of prayer.” Old Pattan is to this day a Hindu city in all but its inhabitants—perhaps one of the most interesting historical spots in Western India. Somnath assumed the appearance it now presents, of a temple evidently of pagan original altered by the introduction of a Mohammedan style of architecture in various portions, but leaving its general plan and minor features unmolested. The temple consists of one large hall in an oblong form, from one end of which proceeds a small square chamber, or sanctum. The centre of the hall is occupied by a noble dome over an octagon of eight arches; the remainder of the roof terraced and supported by numerous pillars. There are three éntrances. The sides of the building face to the cardinal points, and the principal entrance appears to be on the eastern side. These doorways ave unusually high and wide, in the Pyramidal or Egyptian form, decreasing towards the top; they add much to the effect of the building. Internally, the whole presents a scene of complete destruction; the pavement is everywhere covered with heaps of stones and rubbish; the facings of the walls, capitals of the pillars, in short, every portion possessing anything approaching to ornament, having been defaced or removed, (if not by Mahmud, by those who subsequently converted this temple into its present semi-Mohammedan appearance). Externally the whole of the buildings are most elaborately carved and ornamented with figures, single and in groups of various dimensions, Many of them appear to have been of some size; but so laboriously was the work of mutilation carried on here, that of the larger figures scarcely a trunk has been left, whilst few even of the most minute remain uninjured. The western side is the most perfect: here the pillars and ornaments are in excellent preservation. The front entrance is ornamented with a portico, and surmounted by two slender minarets ornaments so much in the Mohammedan style, that they, as well as the domes, have evidently been added to the original building.

A more detailed survey report of Somnath temple ruins was published in 1931 by Henry Cousens. Cousens states that the Somnath temple is dear to the Hindu consciousness, its history and lost splendor remembered by them, and no other temple in Western India is “so famous in the annals of Hinduism as the temple of Somanatha at Somanatha-Pattan”. The Hindu pilgrims walk to the ruins here and visit it along with their pilgrimage to Dwarka, Gujarat, though it has been reduced to a 19th-century site of gloom, full of “ruins and graves”. His survey report states:

The old temple of Somanatha is situated in the town, and stands upon the shore towards its eastern end, being separated from the sea by a heavily built retaining wall which prevents the former from washing away the ground around the foundations of the shrine. Little now remains of the walls of the temple; they have been, in great measure, rebuilt and patched with rubble to convert the building into a mosque. The great dome, indeed the whole roof and the stumpy minars, one of which remains above the front entrance, are portions of the Muhammadan additions. One fact alone shows that the temple was built on a large scale, and that is the presence in its basement of the asvathara or horse-moulding. It was probably about the same size, in plan, as the Rudra Mala at Siddhapur, being, in length, about 140 feet over all. The walls, or, at least, the outer casing of them, having in great part fallen, there is revealed, in several places, the finished masonry and mouldings of the basement of an older temple, which appears not to have been altogether removed when the temple, we now see, was built, portions of this older temple being apparently left in situ to form the heart and core of the later masonry. For several reasons, I have come to the conclusion that the ruined temple, as it now stands, save for the Muhammadan additions, is a remnant of the temple built by Kumarapala, king of Gujarat, about AD 1169.