Uma Maheshwar Temple/Uma Maheshwor Temple Kirtipur,Nepal

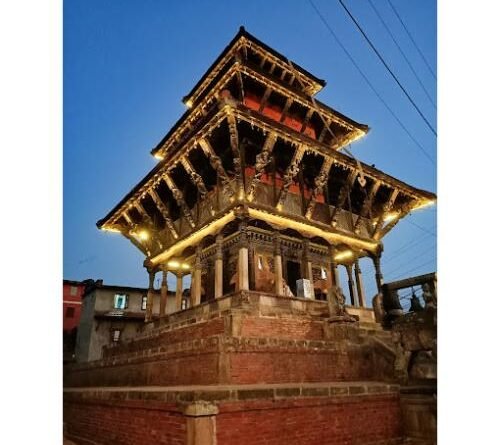

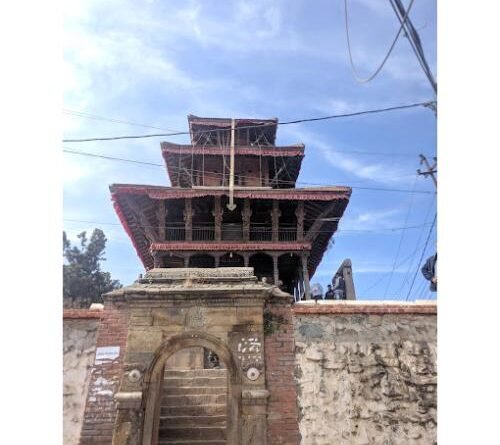

Uma-Maheswor is one of the famous temples in Kirtipur which is also known as Bhavani Shankar. The temple that is 1418m in elevation and offers a great panoramic view of Kathmandu valley and Himalayan range in the north. he temple was constructed during the reign of King Siddhi Narasingh Malla probably in 1655 A.D, in respect of the divine couple, Lord Shiva and his consort Parvati.

Other

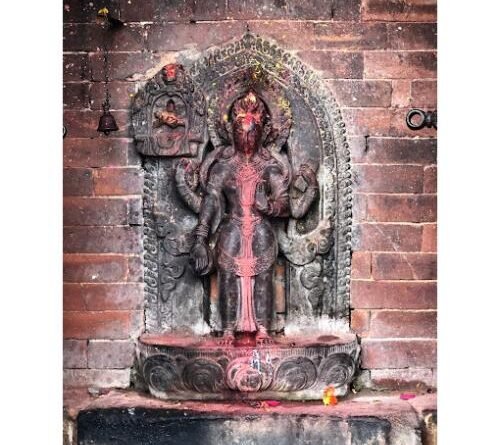

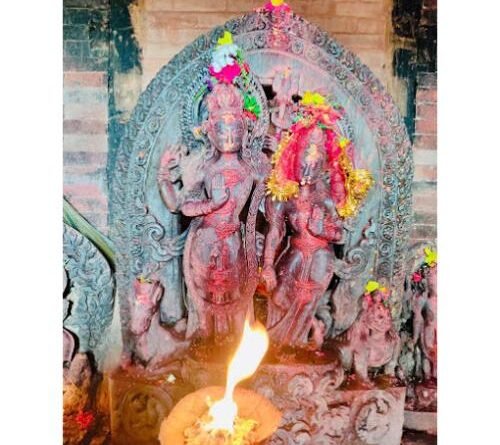

The Uma Maheshwar temple stands on the northwest side of the roughly peanut-shaped hillock that defines Kirtipur. It is an elegant three-story structure commanding fine views of the Kathmandu Valley and the surrounding mountains. The temple’s name derives from the stone icon at its center, depicting Shiva and his wife Parvati in the Uma Maheshwar pose, with Shiva sitting cross-legged and embracing his wife, Uma (Parvati). This icon is also sometimes known as the Bhavani Sankar, suggesting an alternate name for the temple, which never gained popular traction.

The exact age of the temple remains disputed. In his pioneering work from the 1970s, Temples of Nepal, Ron Bernier provided the founding date as 1673 but did not elaborate how he came to that conclusion. More modern research suggests that the temple was extant as early as 1655, as a copper plate mounted on the rear of the main image mentions its donor as a certain Rathaura Bishva Nath Babu, who also made other provisions for the temple. Hence, Shrestha notes that Bernier’s date is likely wrong as “It is very unlikely that the temple would have been built eighteen years after the installment of the image.” (Shrestha, p. 91). However, Shrestha is skeptical that 1655 represents the actual foundation date of the temple, as the copper plate does not describe the donor as the temple’s builder or overall sponsor. More likely, the temple was already in existence and may have been erected in something similar to its present form earlier in the same century or possibly the late 16th century. In any case, given the site’s prominence and vantage point over much of the valley, it seems reasonable that other sacred structures likely predated the Uma Maheshwar; any traces of these former structures—if they once existed—are likely buried out of reach beneath the foundations of the present building.

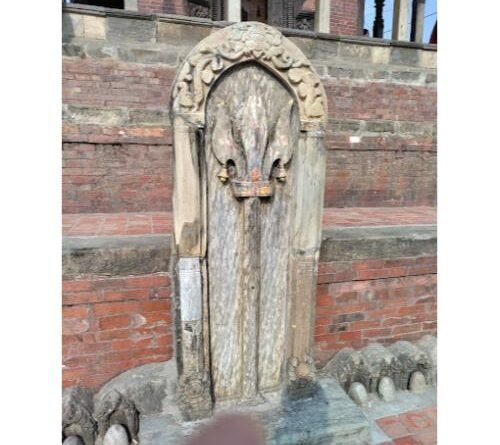

Access to the site is from a long staircase on the southeast side, running up from a small alley in the town below. At the top of the staircase is an arched stone and brick gateway dating from 1715, marking the boundary of the temple. A short walk up another flight of stairs brings visitors into the temple proper. Amid a spacious courtyard paved with brick (which is used by villagers as a convenient sunny location to dry rice, as seen in images 4-12), the temple rises skyward upon a four-tiered brick and stone plinth. A staircase on the southeast side is flanked by stone elephants dating from 1662 and, above them, by statues of Kubara and Bhimsen.

The body of the temple is a typical Newar pagoda built of brick and wood. Its ground floor is square in plan and nearly symmetrical. Originally it was probably open on all four sides, though at some point in the past, three of the four sides were bricked up to create shallow alcoves for images of Devi (south), Durga (west), and Saraswati (north). Only the east entrance remains unobstructed, providing access to the central cella, which is dominated by a large stone image of Shiva and Parvati in the Uma Maheshwar pose, flanked by smaller images of Nandi, Shiva’s bull, and a lion. The interior of the cella is small, intimate, and lightless, apart from ambient light spilling from the door. Its appearance is spartan, with exposed rafters and bare brick walls blackened by centuries of soot.

Outside, the ground-level walls are inlaid with high-quality woodwork comprising the frames, door-jambs, and lintels. Michael Hutt notes that the quarter-round panels that flank the door jambs follow a common theme, each depicting one of the eight mother-goddesses flanked (on the outer edge) by a deity spewing forth from the mouth of a makhara.

The temple’s roof struts are less magnificent than other temples, particularly as the uppermost tier is bare and unornamented. This is likely a consequence of damage sustained in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly as an earthquake in 1833 left the temple bereft of its upper levels (as evidence for this, Shrestha mentions a drawing of the temple from 1855). The temple remained in a battered condition through the earthquake of 1934 but was partly renovated in subsequent years. Only in 1982 was the temple restored to its current state. The carved roof struts on the two lower levels are high-quality conjectural recreations from the 1990s or 2000s. Shrestha does note that two of the original struts from the temple survive but are housed (as of the date of his publication in 1994) in the Ganesh temple at Tunjho, south of the Chilancho stupa.